This post is based on the notes I made watching identically named Artur Holmes lecture in his excellent History of Philosophy course.

Table of Contents

Where it All Begins

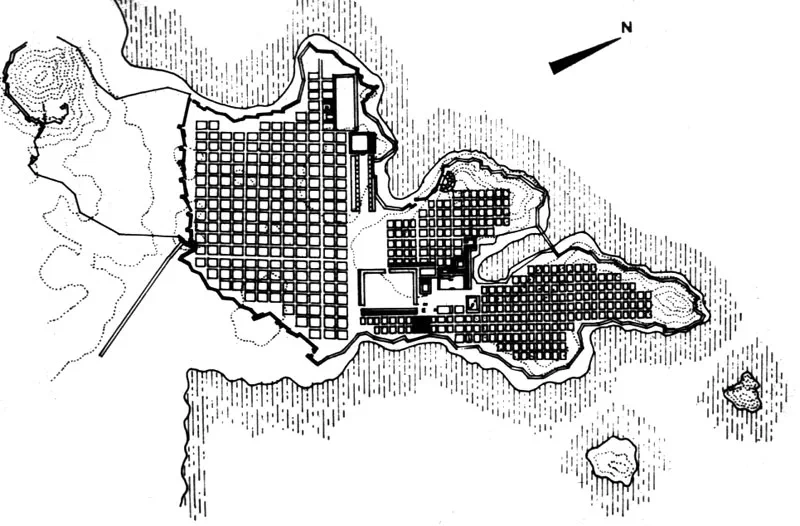

Western philosophy begins with the Greeks, in the Aegean Sea, on the lips of thinkers in Miletus who were building on, but fundamentally breaking from, mythological traditions. The ruins of Miletus are still accessible for tourism, so it looks like a cool travel destination.

Miletus was the wealthiest city in the Greek world, and that’s the key to understanding the origins of philosophy. Wealth creates leisure, and wealth is also generated by trade, which involves cross-cultural exchange. Combine all that and you get a fertile ground for coming up with basic philosophical questions.

The First Philosopher

Thales of Miletus is considered the first known philosopher of the Western tradition. He was a pre-Socratic Greek thinker who proposed that the fundamental principle (or arche) of all things is water. He is also remembered as one of the legendary “Seven Wise Men” of Greece for his practical wisdom, which reportedly included using his knowledge of astronomy to predict a bountiful olive harvest.

Here, we’re getting into Monism, the intuitive idea that everything boils down to a single fundamental building block.

Monism vs Pluralism

The elements battle boiled down to Monism vs Pluralism: how many elements are really basic? There was an initial tendency to look for a single basic element. Thales thought that everything is derived from water: liquid, solid and vapor. It is essential to life. Water is really fundamental to everything. Maybe it’s the basic stuff?

The early philosophers played with different elements: earth, air, fire and water. Those are all popular Greek elements.

Philosophers can be seen as pre-scientific scientists. Early philosophers were obsessed with basic elements, primitive cosmology, and most importantly, morality. Do we have a cosmic justice? Not that different from the Chinese Mandate of Heaven, is it?

Duality

In the late 6th century BCE, two philosophers, Pythagoras and Heraclitus, independently recognized that reality is defined by duality and change.

Pythagoras observed that everything has two opposing aspects: limited and unlimited, odd and even, male and female. He believed these opposites were held together by harmony, which could be expressed through numbers. For him, the universe was an ordered cosmos where opposites coexist in balance.

Heraclitus, on the other hand, was struck by the fact that everything is constantly changing. He used fire as his metaphor: like fire, the world is always consuming and transforming. He also saw that opposites are locked in perpetual tension: life and death, waking and sleeping, but argued that this very conflict creates unity. As he put it, “Harmony consists of opposing tension, like that of the bow and the lyre.”

In other words: both saw two sides to everything. Pythagoras sought the eternal harmony between them, while Heraclitus embraced the perpetual fire of their conflict.

Ethics

A cosmic order also implies the need for an ordered life, and with that realization, ethics enters the stage. The intuitive idea is that if the universe has a rational structure, then human beings, as part of that universe, should align themselves with it.

The Annoying Guy

Zeno was a remarkable figure and he was busy with paradoxes. Change is a paradoxical self-contradictory thing. Hare and tortoise mental experiments, etc. That Zeno guy, he pissed off everyone and no one wanted to follow him. If everything is illusory, why even say that? It’s self-defeating, but he forced later philosophers to try refuting his arguments.

Theology

- Anaxagoras (The Teleologist: Purpose/God/Mind)

- Democritus (The Mechanist: Blind Forces/Chance/Matter)

They created Western agenda. What are the basic stuff. We still ask. Protons, quarks, your choice.

Every major debate in Western philosophy and science can be traced back to the clash between these two fifth century BCE thinkers. They asked the same question, “What is the fundamental nature of reality?”, and arrived at answers that are not only opposite but irreconcilable.

Metaphysics

The Pre-Socratics were the first Western thinkers to ask purely metaphysical questions:

- What actually exists? Only the physical world? Or something beyond it? (Pythagoras pointed to numbers, Parmenides pointed to an unchanging One behind appearances)

- What does it mean for something to be? (Parmenides drew the first stark line between Being and non-Being)

- Is reality one thing or many things? (The Monists said one, the Pluralists said many)

Epistemology

While epistemology becomes the central obsession of the Modern period (Descartes, Hume, Kant), its roots are firmly planted in Pre-Socratic soil. When Parmenides used logic to declare that change is impossible, contradicting his own senses, he forced philosophy to ask: which source of knowledge do we trust? The answer to “What is real?” depends entirely on “How do we know?”

Money?

Miletus was also one of the first places to adopt standardized coinage, and it had its own mint and coin design. The chemical composition and the technology itself was borrowed from the neighboring Lydia. It’s unclear whether there is a link between the birth of abstract money and the birth of abstract thought, but that might not be a pure coincidence.

Conclusion

The introduction to the history of philosophy is pretty dense, and it makes it clear that philosophy doesn’t really advance as quickly as other sciences, if it even advances at all. I mean, all those fundamental questions the early Greeks discovered are still unresolved. It really helps you appreciate the “eternal” stuff, philosophy doesn’t focus on the ephemeral.