Table of Contents

The Common Narrative

We’ve all heard it: “The Fed prints money.” Or “The central bank is injecting liquidity.” Politicians complain about it. Bitcoiners rage against it. It’s become received wisdom in financial discourse.

But it’s mostly wrong. It’s also a convenient distraction that lets the real culprits off the hook.

The story we tell ourselves about money printing is a relic of the gold standard era, when central banks literally minted coins or printed paper currency that could be redeemed for gold. In that world, “printing money” was a direct, mechanical act. Today, things work much differently.

Dual Mandate

Central banks are in fact very limited in their scope. Most are operating under a “dual mandate”, which consists of maximum employment and stable prices.

Needless to say, those two goals are often in conflict, but everything a central bank does is scoped by its mandate. Even if it were able to print money, it would need to justify this action according to its dual mandate.

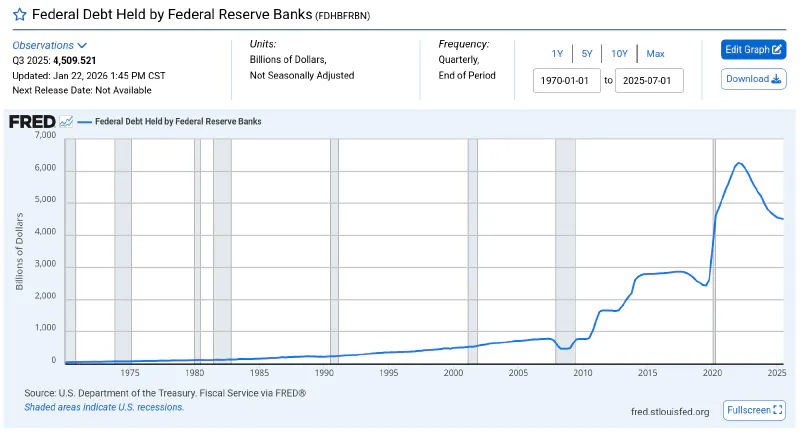

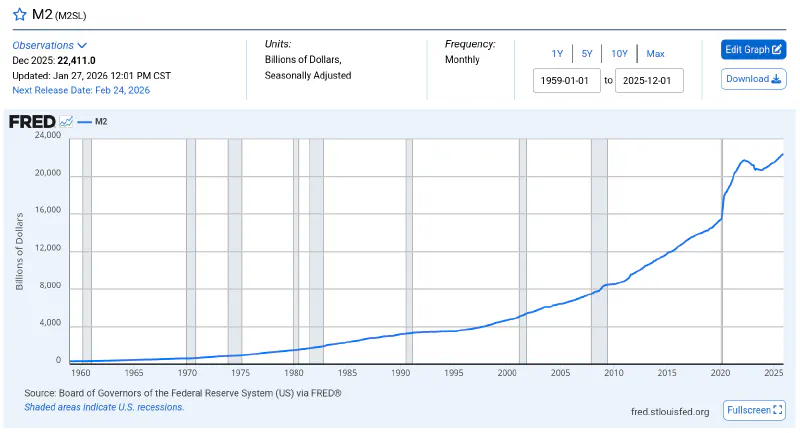

Printing money is indeed at odds with stable prices, since most people believe that inflation is just growth of money supply. This idea gained even more followers after the COVID pandemic, since we saw a clear bump in both inflation and money supply. Also note that QE didn’t trigger high inflation in the years immediately after 2008, which confused many monetarists, precisely because the created reserves sat idle rather than circulating.

What Actually Happens

Modern central banks don’t operate printing presses to fund government spending directly. That job belongs to “the market”, mostly. When the U.S. government runs a deficit, it issues Treasury bonds at auction. Primary dealers (banks, investment funds, foreign entities) buy these bonds. The government spends the proceeds. This is the official mechanism.

But here’s the trick: the central bank is the biggest player in the government bond market. When the Fed conducts QE, it’s buying government bonds on the secondary market, from banks that already hold them. This isn’t direct financing, but the effect is almost identical. By keeping demand high and yields low, the Fed effectively enables larger deficits than the market would otherwise tolerate.

What the Fed Actually Accomplishes

But here’s the crucial question: why does the Fed buy these bonds in the first place? Is it giving banks “fuel” to lend more?

No. Swapping $100 of bonds for $100 of reserves does not increase a bank’s lending capacity at all. Here’s why:

Banks are constrained by capital, not reserves. Capital is the bank’s own money (equity, retained earnings) that absorbs losses. Regulators require banks to hold a certain percentage of capital against their loans. If a bank has $10 in capital and a 10% capital requirement, it can create at most $100 in loans. Exceed that, and regulators step in.

Reserves never appear in this equation.

Before the Fed’s purchase, the bank held $100 in Treasury bonds. After the purchase, it holds $100 in reserves at the Fed. Both are zero-risk assets. The bank’s capital position hasn’t changed. Its ability to lend hasn’t changed.

So what did change?

- Liquidity Reserves are more liquid than bonds, they’re essentially cash at the central bank.

- Interest rates By buying bonds, the Fed pushed prices up and yields down, making borrowing cheaper across the economy.

- Bank balance sheets stability During crises, even safe assets can be hard to sell. The Fed provided certainty.

The bank didn’t gain new lending power. It just exchanged one zero-risk asset for another, while the Fed used the transaction to achieve its broader policy goals.

The Semantic Distraction

Here’s where it gets interesting. Critics say QE is “printing money” because it increases the monetary base. They’re not entirely wrong about the effect, but they’re completely wrong about the mechanism.

The central bank can flood the system with reserves, as it did after 2008, but if there’s no loan demand, or banks tighten lending standards, the money supply doesn’t explode. This is exactly what happened post-2008: massive QE, but inflation stayed low. The reserves sat on bank balance sheets.

This distinction matters. When people say “the Fed prints money,” they’re imagining a direct transfer: government prints, government spends. That’s not what happens. What’s actually happening is far more abstract, and arguably more dangerous.

The Dangerous Part

The real problem isn’t printing. It’s credit creation, and private banks do most of it.

When banks make loans, they create money. Your mortgage didn’t come from some pool of pre-existing savings. The bank created it, at the moment of lending, by typing numbers into your account. The money didn’t exist before you borrowed it. Now it does.

This is also why attacking the Fed misses the point. The real “printing press” is the ledger system banks run. They are the ones creating money out of thin air every time they approve a loan. The central bank indirectly enables it, yes. But the banks are the ones pulling the trigger.

Why This Confusion Persists

The “printing money” narrative is appealing because it’s simple. It maps onto our intuitive understanding of physical currency. It also serves political purposes: it gives critics a target (the evil central bank printing to fund deficits) and gives bitcoiners a cause (sound money vs. fiat paper).

Bitcoin fixes this differently. Its supply is algorithmic, not credit-based. When you receive a bitcoins, it’s not someone else’s loan. It’s a genuine transfer of a scarce, independently verified asset. No reserves required, no fractional reserve lending, no bank-ledger creation.

The Self-Sovereignty Question

When the money supply expands, it’s not just an economic act. It’s a political one. It transfers wealth from savers to borrowers via inflation. It distorts price signals. It rewards the connected and punishes the prudent.

The ability to create money is the ultimate form of power over others. In the old days, only kings had it. Then governments delegated it to central banks, which were supposed to be independent. But private banks have always been the true creators.

The blame game is deliberate. Blame the Fed, and you ignore the banks. Blame “printing,” and you ignore the ledger entries that actually expand the money supply. Who controls the money supply? Technically, the central bank. Practically, the commercial banks, and they have every incentive to keep creating credit, because that’s how they earn profits.

Conclusion

The Fed buys bonds not to “fuel lending” but to manage interest rates, provide liquidity, and stabilize markets. Swapping bonds for reserves changes nothing about a bank’s lending capacity, that’s governed by capital, not reserves.

The narrative of “printing” is a distraction. It lets us blame a single institution for a system where both central banks and private banks are complicit. The Fed provides the liquidity and sets the rates, the banks provide the actual credit creation. Both are responsible for the inflation, the bubbles, and the transfer of wealth from the many to the connected few.

If you want to understand modern money, forget the printing press. It’s a database now. And like all databases, it’s controlled by whoever has the keys, which, in this case, is a coordinated alliance of central bankers and commercial bankers.